Remember our troubling past

Hanging Rock is haunted by a convenient fiction rather than an uncomfortable truth.

In comparison to the considerable information made available to tourists about the fictional schoolgirls’ disappearance at Hanging Rock, there is scant material about actual First Peoples losses and traumas that have occurred in the area since colonisation.

With the arrival of European invaders, First Peoples of the region - the Wurundjeri, Taungurung and Djarra peoples of the Kulin Nation - were exposed to introduced diseases, such as deadly smallpox outbreaks, or were killed for resisting invasion and displaced by early colonisers. In the later half of the 19th Century, First Peoples who survived were relocated to missions, such as the Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve in Healesville. This history of violence, abuse, forced removal, destruction of culture, invasion and theft of Kulin Country is cursorily mentioned or ignored in heritage information at the site.

The Miranda Must Go campaign calls for the acknowledgement of the negative impact of European colonisation at Hanging Rock and surrounds. Hanging Rock visitors should be haunted by this history of dispossession and violence, rather than the mythic vanishing of white schoolgirls.

Remove the white vanishing myth

Picnic at Hanging Rock is obsessively retold and reaffirmed at Hanging Rock.

The local tourist industry capitalises on Hanging Rock’s association with Joan Lindsay’s novel, Picnic at Hanging Rock. Tourist pamphlets and road signs are branded with the slogan “Experience the Mystery”. The interpretive Discovery Centre at the foot of Hanging Rock dedicates considerable display space to the myth, while marginalising First Peoples connection to the site and the impact of colonisation. Until 2021, Peter Weir’s film adaptation was screened outdoors annually around Valentine’s Day (the days the girls go missing in Lindsay’s novel) at the Hanging Rock Reserve. In 2017 Fremantle Media and Foxtel filmed at the site a six-part miniseries adaptation of Picnic at Hanging Rock starring Natalie Dormer. In 2018 the public was encouraged to dress up as Miranda in white frocks to participate in a community dance flash mob at Hanging Rock called Too Many Mirandas.

In White Vanishing: Rethinking Australia’s Lost-in-the-Bush Myth theorist Elspeth Tilley has written about the prevalence of the white vanishing myth in Australian culture, stating that the persistence and repetition of this trope “is engaged in a strategy of forgetting and displacing the non-white, and installing itself as a constituent of the dominant national mythology” (2012, p. 35).

The Miranda Must Go campaign demands the end to the habitual retelling of Lindsay’s story at Hanging Rock. We seek a decolonialised future for the significant landmark which does not overwrite Kulin Country with white vanishing.

Rethink the stories we tell at Hanging Rock

The wrong losses and absences are commemorated at Hanging Rock.

Cataclysmic disruptions to First Peoples way of life, sovereign relation to Country and capacity to practice culture following colonisation has severly impacted First Peoples continuing cultural connection to Hanging Rock. Three First Peoples groups—Wurundjeri, Taungurung and Djarra—have boundaries close to Hanging Rock and it is understood the site was once an important ceremonial meeting place for gatherings between the groups. The damaging effects of colonial occupation, however, means that the transmission of oral history, story and cultural connection to Country has been damaged, and First Peoples need time, resourcing and access to Country to reconnect, heal and revitalise culture.

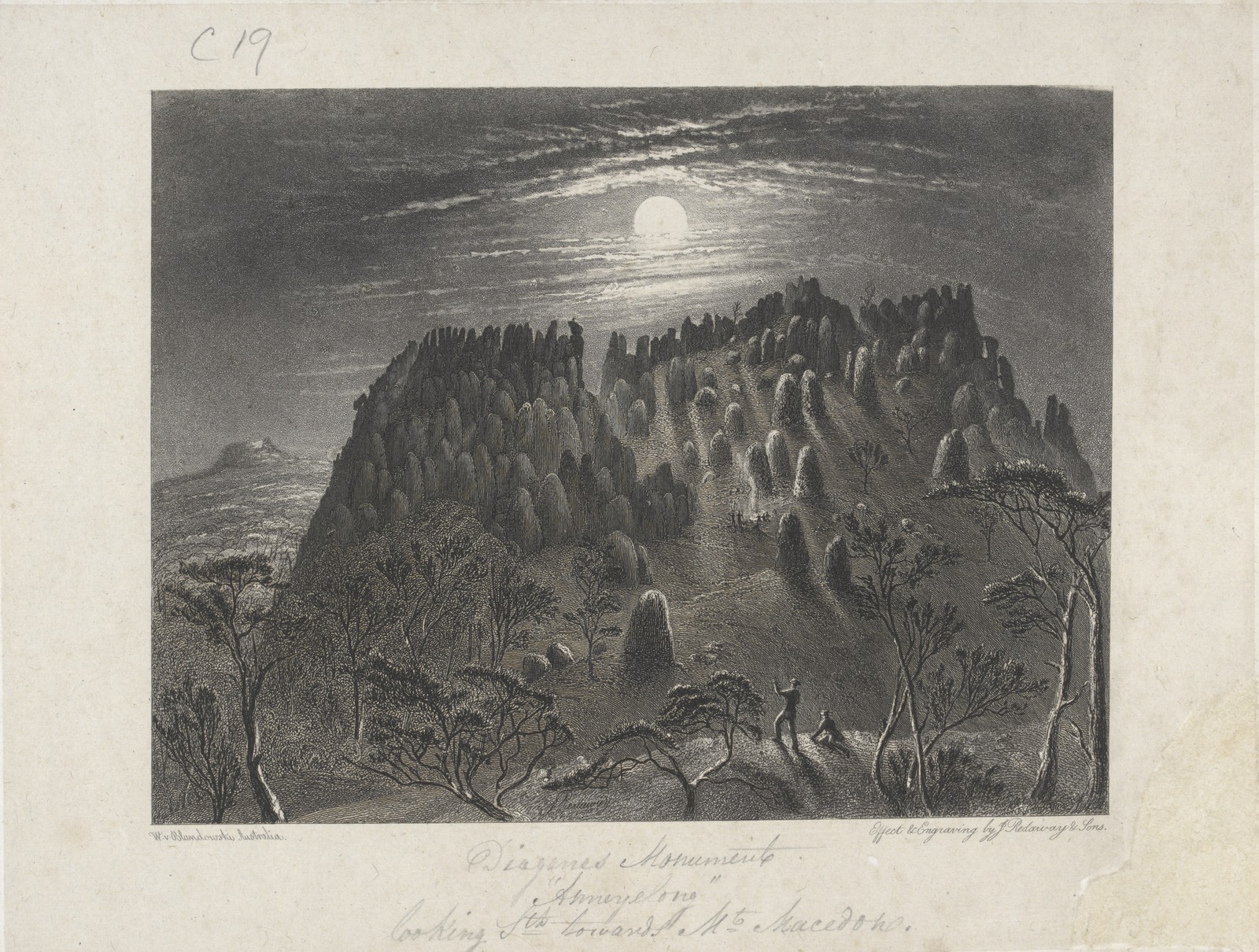

These damaging effects have stalled efforts to recoup Hanging Rock’s original name. While at least six European names – ‘Mount Diogenes’, ‘Diogenes’ Head’, ‘Diogenes Monument’, ‘Dryden’s Rock’, ‘Dryden’s Monument’, and ‘Hanging Rock’ – have been documented for the site, there is just one known surviving record of a name used by First Peoples. An engraving of Hanging Rock by German naturalist, William Blandowski, made during an expedition in 1855/56 records the word “Anneyelong”. Linguists and historians believe Blandowski misheard Kulin Peoples’ pronunciation, and the name was possibly “Ngannelong” or something similar.

This campaign recognises that efforts to restore First Peoples language and stories on Country are urgent and vital. The Miranda Must Go campaign also demands that non-Indigenous Australians confront evidence of disrupted knowledge and openly recognise them as distressing consequences of colonial invasion of First Peoples Country. The stories that should trouble us at Hanging Rock should be these real First Peoples’ traumas and struggles, not white lost-in-the-bush myths.

Hanging Rock is haunted by a convenient fiction rather than an uncomfortable truth.

In comparison to the considerable information made available to tourists about the fictional schoolgirls’ disappearance at Hanging Rock, there is scant material about actual First Peoples losses and traumas that have occurred in the area since colonisation.

With the arrival of European invaders, First Peoples of the region - the Wurundjeri, Taungurung and Djarra peoples of the Kulin Nation - were exposed to introduced diseases, such as deadly smallpox outbreaks, or were killed for resisting invasion and displaced by early colonisers. In the later half of the 19th Century, First Peoples who survived were relocated to missions, such as the Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve in Healesville. This history of violence, abuse, forced removal, destruction of culture, invasion and theft of Kulin Country is cursorily mentioned or ignored in heritage information at the site.

The Miranda Must Go campaign calls for the acknowledgement of the negative impact of European colonisation at Hanging Rock and surrounds. Hanging Rock visitors should be haunted by this history of dispossession and violence, rather than the mythic vanishing of white schoolgirls.

Remove the white vanishing myth

Picnic at Hanging Rock is obsessively retold and reaffirmed at Hanging Rock.

The local tourist industry capitalises on Hanging Rock’s association with Joan Lindsay’s novel, Picnic at Hanging Rock. Tourist pamphlets and road signs are branded with the slogan “Experience the Mystery”. The interpretive Discovery Centre at the foot of Hanging Rock dedicates considerable display space to the myth, while marginalising First Peoples connection to the site and the impact of colonisation. Until 2021, Peter Weir’s film adaptation was screened outdoors annually around Valentine’s Day (the days the girls go missing in Lindsay’s novel) at the Hanging Rock Reserve. In 2017 Fremantle Media and Foxtel filmed at the site a six-part miniseries adaptation of Picnic at Hanging Rock starring Natalie Dormer. In 2018 the public was encouraged to dress up as Miranda in white frocks to participate in a community dance flash mob at Hanging Rock called Too Many Mirandas.

In White Vanishing: Rethinking Australia’s Lost-in-the-Bush Myth theorist Elspeth Tilley has written about the prevalence of the white vanishing myth in Australian culture, stating that the persistence and repetition of this trope “is engaged in a strategy of forgetting and displacing the non-white, and installing itself as a constituent of the dominant national mythology” (2012, p. 35).

The Miranda Must Go campaign demands the end to the habitual retelling of Lindsay’s story at Hanging Rock. We seek a decolonialised future for the significant landmark which does not overwrite Kulin Country with white vanishing.

Rethink the stories we tell at Hanging Rock

The wrong losses and absences are commemorated at Hanging Rock.

Cataclysmic disruptions to First Peoples way of life, sovereign relation to Country and capacity to practice culture following colonisation has severly impacted First Peoples continuing cultural connection to Hanging Rock. Three First Peoples groups—Wurundjeri, Taungurung and Djarra—have boundaries close to Hanging Rock and it is understood the site was once an important ceremonial meeting place for gatherings between the groups. The damaging effects of colonial occupation, however, means that the transmission of oral history, story and cultural connection to Country has been damaged, and First Peoples need time, resourcing and access to Country to reconnect, heal and revitalise culture.

These damaging effects have stalled efforts to recoup Hanging Rock’s original name. While at least six European names – ‘Mount Diogenes’, ‘Diogenes’ Head’, ‘Diogenes Monument’, ‘Dryden’s Rock’, ‘Dryden’s Monument’, and ‘Hanging Rock’ – have been documented for the site, there is just one known surviving record of a name used by First Peoples. An engraving of Hanging Rock by German naturalist, William Blandowski, made during an expedition in 1855/56 records the word “Anneyelong”. Linguists and historians believe Blandowski misheard Kulin Peoples’ pronunciation, and the name was possibly “Ngannelong” or something similar.

This campaign recognises that efforts to restore First Peoples language and stories on Country are urgent and vital. The Miranda Must Go campaign also demands that non-Indigenous Australians confront evidence of disrupted knowledge and openly recognise them as distressing consequences of colonial invasion of First Peoples Country. The stories that should trouble us at Hanging Rock should be these real First Peoples’ traumas and struggles, not white lost-in-the-bush myths.

Diogenes Monument “Anneyelong” looking Sth towards Mt Macedon, by W. V. Blandowski, effect & engraving by J. Redaway & Sons (1855-1856), State Library Victoria.